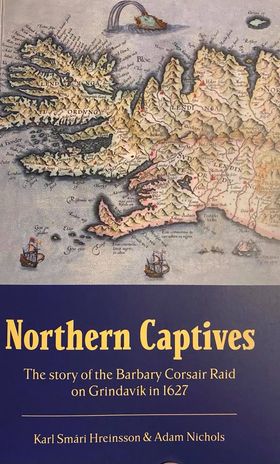

The story of the Baraby Corsair Raid on Grindavík in 1627

Shipping incl.

BOOK REVIEW

By Torbjørn Ødegaard

Karl Smári Hreinsson & Adam Nichols: Northern Captives. The story on the Barbary Corsair Raid on Grindavik in 1627. Saga Akademia, Keflavik, Iceland (2020). 209 pages.

While professor Emeritus Thorsteinn Helgason, of the University of Reykjavik, has discussed academically the sources of, and attempted to give a traditional historical analysis of, the so-called «Turkish Raid» on Iceland, (The Corsair’s Longest Voyage, published by super-expensive Brill, Leiden, 2018), the two popular writers, Karl Smári Hreinsson from Iceland and the US professor Adam Nichols, have recently presented a far more vivid summary of the dramatic and violent events in Grindavik, in southeast Iceland, in that very unusual summer of 1627.

The 1627 corsair raid has mistakenly been labeled the «Turkish Raid». In fact, the two separate expeditions simultaneously sent against Iceland in the North Atlantic originated in North Africa: one from Morocco, led by the Dutch convert Murad Reis, attacked Grindavik and some few sites at the western part of Iceland; the other, also manned by ex-Christians, but from Algiers, attacked the eastern fiords and the Westman Islands. By August, something like 380 Icelanders, as well as some few Danish sailors taken during the raids, were sold in the slave markets in Algiers and Salé.

The masterminds of the attack were not native-born Turks and probably not even Muslims by heart, but rather «Turks by profession», which was the informal title given to those important sea-skilled European navigators and able-bodied sailors who «turned Turk», i.e., converted and became Muslims, in the Maghreb during a 300-year period (approx. 1530–1830), from the time of the Barbarossas until the French invasion of Algiers.

The converts — or, rather, the «renegades», if a European is asked — had once themselves been captives taken at sea by the «Turks» of the Maghreb and later gained freedom by embracing Islam and ended up manning the decks and masts of North African corsairs ships, robbing European vessels of men and cargo. Even the simple idea of sailing against Iceland is said to have originated from a Danish or Norwegian slave in Algiers, who, in such a way, hoped to ransom himself from «Barbary slavery» (according to one source, this «informant» later died in a battle at sea, still in the service of the Turks).

The Commander on the Moroccan ship that attacked Grindavik, Murad Reis (alias Jan Jans from Haarlem, Holland), was one of those «Turks by profession», whose life is currently being puzzled together by one of the authors, Adam Nichols, who is preparing a biography of this amazing cross-cultural survivor and admiral of the Salé rovers in the 1620s.

On Murad Reis’ ship there were absolutely no Turks (since Morocco was outside the dominance of the Ottoman Empire), but only converts and slaves. In fact, there is a fair chance that it was a completely non-Muslim crew, since a Christian renegade, surviving in North Africa only by changing religion, could hardly be regarded as a true Mohammedan. When later taken by the Spaniards at sea and put into the dungeons of the Inquisition, they willingly jumped back. There are many examples of Muslim-European sailors that easily turned Christian again, only for the sake of saving their own lives, as they also did when they «turned Turk».

The attack on Danish-ruled Iceland was nevertheless referred to as the «Turkish Raid», a suitable term in one sense, since the slowly expanding Ottoman Empire in the year of 1627 was still a real threat against Europe. This branding has been followed up by an endless line of misleading and uncritical books, articles, and films about the «terrible Turks» from the Barbary Coast and the Christian victims of their sea-terror, a construction that later platformed the misleading Bernhard Lewis-invented idea of «maritime jihad».

It was instead an internal European maritime guerrilla war. Unlucky, poor, young, and opportunistic — originally both protestant and catholic — sailors, under the flags of Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli, and Salé, plundered their fellow countrymen for three centuries. Many of them refused a return to Europe and a following reintegration into Christianity, as did the above-mentioned Murad Reis, who once visited his homeland in Holland as a free man and a new «Muslim», but preferred returning to his life as Admiral in Salé and so waved a final good-bye to his true Dutch wife and children, who had visited him in hopes that Murad Reis would turn into Jan Jans again. It never happened. An Italian renegade in Algiers in the time of the «Turkish Raid» — the famous and powerful Ali Pitchin — is said to have laughed openly at the Muslim’s belief and their frequent prayers, while at the same time always keeping his young male slaves indoors, for fear of the almost ritualized sodomy performed by the Turkish janissaries upon young and defenseless Christian captives. Murad Reis was probably a man of the same irreligious sort: a Muslim by name and clothing, but only as a covering for the black soul of a pure pirate.

The story of the renegades has been well studied, for example by Lucile and Bartolomé Bennassar (Les Chrétiens d’Allah, edited several times), but from a European viewpoint, a self-critical aspect is missing in most European studies, partly also in writings about the Icelandic «Turkish Raid», at least when it comes to the completely inaccurate notion of a Turkish connection — even though we are aware of the fact that, in the early modern period, the word «Turk» was a synonym for Muslim. Unpleasant though it may be for many Western readers, the pirates of Algiers and the rovers of Salé were to a large extent our own guys. A Dutch diplomat in Algiers in the 1620s compiled a list of the reises (captains) and included their home ports. Around 50 percent of the corsair captains had a non-Muslim European background.

Back to the raid itself: an insignificant event could have halted the whole Murad Reis project, as happened on the Faroes in 1629, when one or two «Turkish» ships wrecked there after hitting a rock. The crew and the slaves aboard all died. The name of the place has survived and is today called «the Turkish Tomb». Murad Rais’ ship stranded in the harbor at Seylan, in Iceland, two years earlier. In this case, though, cargo and prisoners were removed by the experienced sailors, and the Moroccan ship floated free of the underwater snag and continued its voyage back to Salé. It could easily have been wrecked, reminding us that history is a collection of all those random and apparently insignificant pieces systematically put together and later analyzed by learned folks. With a different tide, our story could have had a completely different outcome.

But captain Murad Reis successfully returned home (in convoy with a seized Danish ship) and the authors Hreinsson & and Nichols provide a clear description of this remarkable corsair city on the Atlantic coast of the weakened empire of Morocco. Reading their Grindavik story, we are elegantly taken inside the walls of multicultural Salé: Arabs, Berbers, high and low-ranked corsairs, slaves, Moriscos from Spain, Africans from the other side of the Sahara, etc. Around 1000 ships were taken by the Salé corsairs in the 1620s. Ten percent of the city’s population was European slaves, in number around 1500.

The authors’ work with the historical context might be a little exaggerated, especially when it comes to the background of the Hornacheros in Spain, a stubborn group of Spanish Muslims, who, like thousands of other Moriscos, had to give up and finally ended up in Salé. Needless is also multiple referring to what comes in the coming chapter or what has been written in one of the former — small unnecessary technicalities that an editorial board should have omitted.

When Murad Reis’s ships returned to Salé, the locals celebrated the booty they brought in. It would be very interesting to know more about the corsair crew, but sources are nonexistent: there are no crew lists, no payment rolls with names, age, place of birth, and function on board. While most Icelandic captives can be identified by their given names by birth, there is a great lacune when it comes to the composition of the Salé crew and their origin. Again our question: Were they all Europeans, born in Scandinavian, English, German, and Dutch coastal cities?

When it comes to life and society, especially on the slaves’ daily life, Hreinsson & and Nichols — like most other «Barbary» writers —make extensive use of contemporary printed works written by ransomed slaves and travelers (among others, Joseph Pitts, Thomas Pellow, Germain Moüette, and Adam Elliot), giving the necessary context and color. Common features for the unfree part of the Salé population were mistreatment and hard work, witnessed to by several of the 60–70 Icelanders who were there in the late 1620s. Many slaves spent their nights in the city’s mattamores, which were terrible and filthy underground prisons. One of these mattamores is today preserved in Morocco as a protected UNESCO site and can be seen in the old imperial city of Meknes. Two German tourists did their own private tour in the Meknes mattamores some years back. They became lost in the complexities of the subterranean construction (which is as large as two football fields), and the unlucky two were never seen again.

In Northern Captives, the story of the Icelanders enslaved in Salé focuses on Gudrun Jonsdottir, her two brothers (Halldor and Jon) and her three sons (Helgi, Hedinn, and Jon the Scholar), all from Jarngerdarstadir farm near Grindavik. What is missing in the academic work of the «Turkish Raid» expert Thorsteinn Helgason («the grand old man» within this limited scholarly field) appears more clearly in Hreinsson & and Nichols, which is to convey what the Icelandic sources tell us about the fate of the Icelanders on Muslim soil. Who bought them? How were they treated? How much did they cost at the slave market? What was their slave labor like? What did they write in the letters back home? All this lively information is often given low priority in PhDs and more traditional academic works, but is fortunately present in popular non-fiction literature like Northern Captives.

One of the best parts of Hreinsson & Nichols is undoubtedly the reconstruction of the remaining members of the above mentioned Jarngerdarstadir farm family. Relevant quotations from the Quran and seventeenth-century Barbary prisoners’ memoirs throw light on the possible life of poor Hedinn, Gudrun Jonsdottir’s youngest son. Employing different secondary sources, the authors mention two consistent factors regulating a young slave’s life in seventerenth-century North Africa: he or she was regarded as either a possible Muslim (since kids converted easily) or as a sexual object, to be abused by male owners. Most of the contemporary printed texts on North Africa before the colonial time have passages on the widespread practice of pedophilia. Hedinn was around seven years old when he was sold in Salé to the same man who bought, and soon released, his mother and uncle — and those two adults only. Together with a young Icelandic girl, the child Hedinn was left alone in a stranger’s house, with a very insecure future. He might have been one of several thousand young European victims of such «Turkish» atrocities. But he might as well have had a fairly decent upbringing. In 1633, his brother Jon «The Scholar» wrote a letter from Algiers, saying that Hedinn — then a teenager — was a ship’s carpenter and a free man in Salé — and probably a Muslim. Thanks are due to Hreinsson & Nichols for presenting these personal stories, which they reconstruct by using a set of international sources, in addition to printed documents in source-editions or unprinted primary sources, to reveal the possible outcomes of the captive Icelanders’ lives and personal experiences in the Barbary States (the old and frequently used name for the Maghreb before 1830, used mostly by Europeans). There were two Jon Jonssons brought to Salé from Grindavik: Gudrun’s brother, who for years ploughed a vineyard somewhere in the Salé region and later died in Salé or Algiers (the sources are unclear); and Gudrun’s eldest son Jon «The Scholar», who was sold from one man to the other, until both he and his brother Helgi (Gudrun’s middle son) ended up in Algiers, not very far from each other.

The ransom part is equally interesting. Gudrun and her brother Halldor were back in Iceland by 1628. They spent less than a full year in North Africa. There are few details on the ransom of the siblings, but an anonymous Dutchman had been involved, obviously in a very remarkable and completely unknown way. Few of the 380 captive Icelanders came home that quickly. The last to be ransomed was a small group from Algiers in 1645, and in that year there were — quite unbelievably — still Icelanders in North Africa, both slaves and converts.